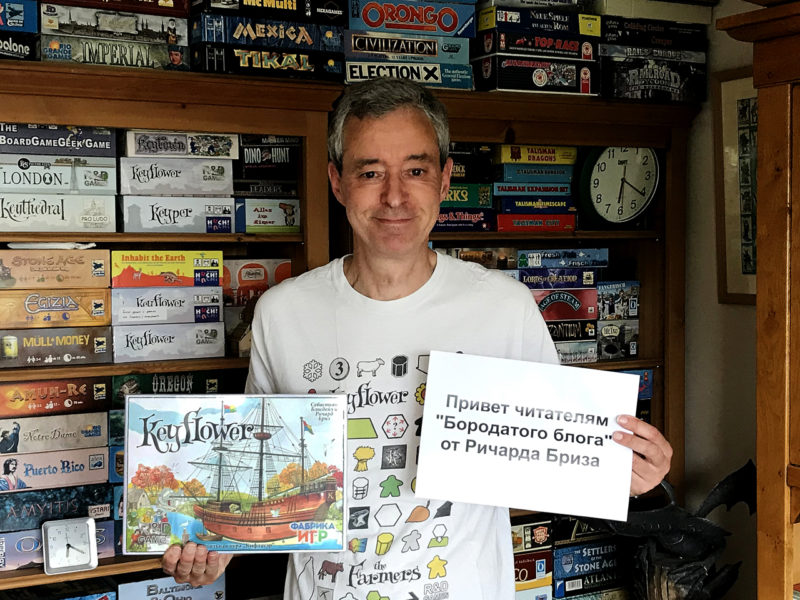

«Keylower», even though it was released back in 2012, is still sitting pretty comfortably among the top 100 best games according to BoardGameGeek. Whether this is something the game deserves (or not) is going to be the topic for another conversation another time. Instead, today we have contacted Richard Breese, one of the designers who worked on Keyflower and the creator of pretty much the whole Key series.

His name is not too well known among the tabletop community comparing to other «celebrities», nevertheless his contributions to game development should be appreciated, and he does have things to tell. So do not let me distract you any further. Enjoy!

Hello Mr. Breese. Thank you for sparing some time for this interview.

Thank you for your interest.

Well, let’s start. First, tell us a little bit about yourself. Who is Richard Breese? What do you do when you’re not busy designing board games?

I’m a 63-year-old English man. I’ve lived in Stratford upon Avon, birthplace of William Shakespeare, for the past 20 years and previously in London. I’m a Chartered Accountant by profession and have been designing and publishing boardgames for 30 years.

I still work part-time as Finance Director for a commercial property development company. I enjoy time with my family, running and cycling and, of course, playing board games.

How did you become interested in board games?

My parents had a selection of traditional board games which we played when I was a child. «Monopoly», draughts, chess, «Coppit», «Connect Four» and similar family games which I enjoyed, plus card games such as Canasta and whist.

When made you try your hand in design?

I created some games as a child. But my first published self-published game «Chamelequin» was initially inspired by games of «Dungeons and Dragons». I attributed different movement abilities to the different character classes and eventually reduced this down to an abstract game.

The gaming world was a lot smaller 30 years ago with only twenty or so new gamers’ games launched at each year at Spiel.

I exhibited the game at the London Toy Fair where I met Brian Walker, editor of a UK boardgames magazine Boardgames International, and Ian Livingstone, co-founder of Games Workshop, who suggested I should go to Spiel, at Essen. I hired a stand there the following year in 1991 and discovered the world or ‘German’ games, or Eurogames as they are now referred to. The gaming world was a lot smaller 30 years ago with only twenty or so new gamers’ games launched at each year at Spiel. I enjoyed these new games with their interesting mechanics and themes and was motivated to start designing my own games in this style.

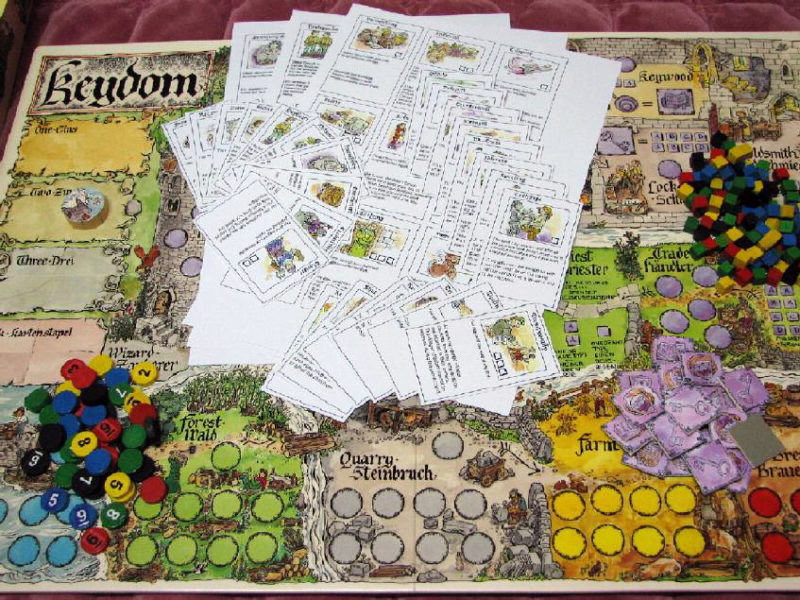

Somewhere within BGG you mentioned you released a game that is recognized to be the first to use worker placement mechanism. What game was it?

«Keydom» is widely recognised as the first worker placement game. The game was subsequently re-issued as «Morgenland» in Germany and «Aladdin’s Dragons» in the US.

How did you come up with this mechanism?

The mechanism evolved from my plays of «Settlers of Catan». In that game resources are obtained from being adjacent to the correct terrain hexes, but only when the correct dice number is removed. I wanted to create a mechanism where resources were obtained through player choice and not through the luck of a dice roll.

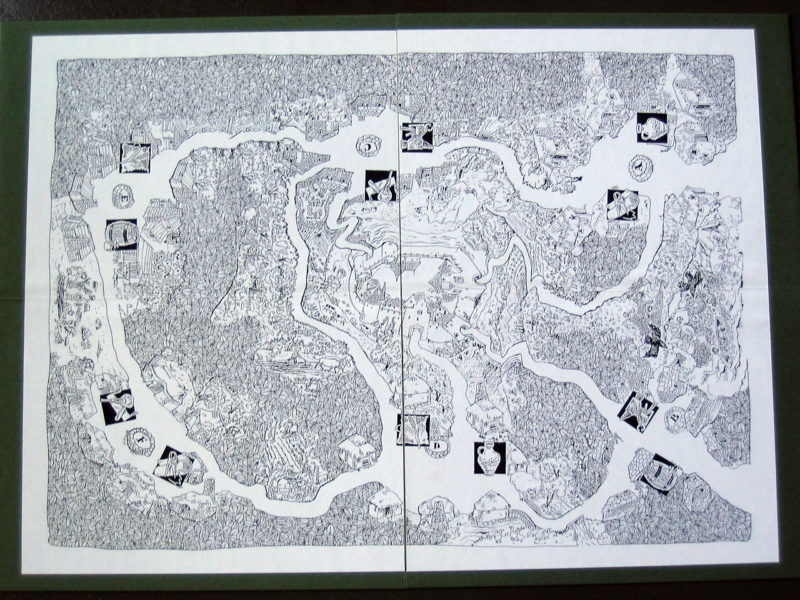

Your name is closely associated with the games set in the ‘Key’ universe. What is the Key universe? How was it created and where is it going to?

«Keywood» was my first Euro-style game, with just 200 home-made copies. I was looking for a name for the game, which has a regal benevolent leader, and met an American gamer called Keywood Cheves at Spiel in 1994. His persona fitted the bill and his unusual name was perfect for the game. I alerted Keywood after the game was published and fortunately, he was quite pleased and ordered 6 of the copies. He was even more please at the subsequent collectability of the game. Copies have now sold for €1,200 and Keywood admitted he had sold one of his copies.

«Keywood» was set in Keydom, which was the title of the second Key game. It was my fortune that the first half of the name ‘Key’ was such a convenient prefix. «Keydom» and the subsequent Key games all have similar characteristics. They are all (apart from «Key to the City – London») set in the medieval Key universe, player actions are positive, the interaction is through the game mechanism, not direct against another player and there is only a small amount of luck in the games.

The games follow a loose story. In «Keywood» (1995) players attempt to settle and govern the new land Keydom. In «Keydom» (1998) is settled and a leader sought. Players acquire artifacts to support their claim inherit the throne. In «Key Town» (2000) the inhabitants gain further skills and experience as churchmen, councilors, and tradesmen, bringing with them seniority, prestige, and high standing amongst their peers. «Keythedral» (2002) the inhabitants build the Keythedral.

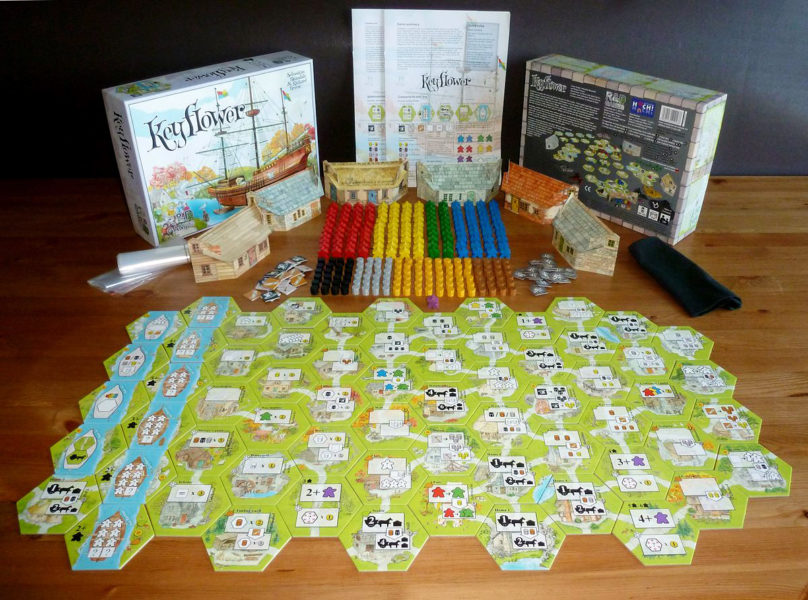

In «Key Harvest» (2007) the fields of the Keydom are connected and harvested. «Key Market» (2011) attempt to turn their initial scanty resources into a thriving economic system. In «Keyflower» (2012) and the «Farmers» (2013) and «Merchants» (2014) expansions and «Key Flow» (2018) the inhabitants set sail to, land in and develop a new territory. In «Keyper» (2017) the inhabitants work together to further develop their farms and villages.

The Key world is likely to evolve further in the next couple of years.

One of the distinctions of the Key series are the illustrations by Juliet Breese. How did your collaboration start? It seems that the artist position was taken by Vicki Dalton. Was there a reason for the change?

Juliet is my sister and was an illustrator by vocation. However, she retired from illustrating a couple of years ago so I asked Vicki to take over the task. I had known Vicki a number of years as her parents Alan and Charlie Paull are gamers, who have their own company Surprised Stare games, and have been playtesters for the R&D games since we first met at Spiel in 2002.

In your opinion, what aspects you did right in the games that preceded «Keyflower» and what should have been done differently?

I am generally happy with the pre-Keyflower games, which are mentioned briefly in the answer before last. However, I think the early games were ‘of their time’. The boardgame world has evolved enormously over the past 30 years and I think have generally games have got better during that period, as games have built on the ideas and mechanisms of earlier games.

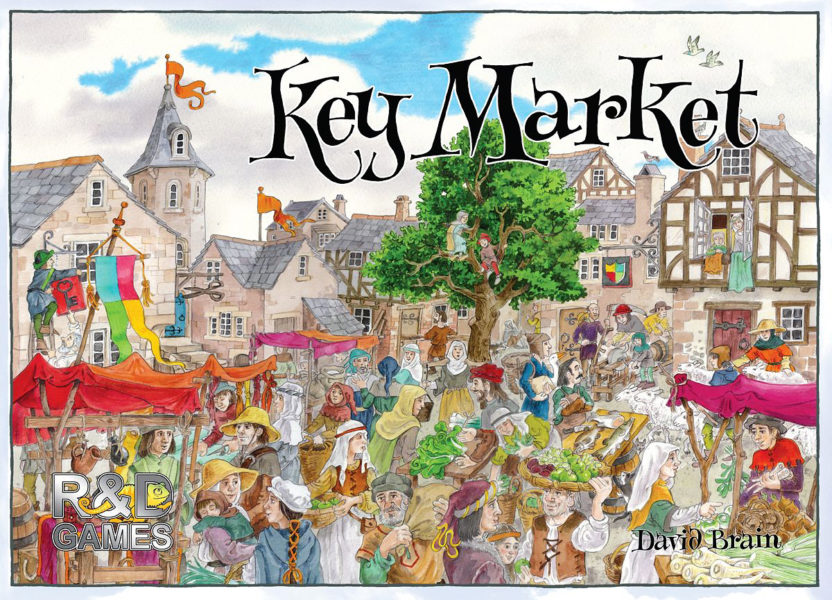

It was David Brain who designed «Key Market». Why one of the games in the Key series was designed by somebody else and not you?

The development story is told in full by David on the sides of the «Key Market» box bottom. David had play tested some if my earlier games and I had the opportunity to play his game «Book of Hours» – which subsequently became «Key Market». I had a gap in my schedule and suggested to David that we worked further on his design. I probably spent more time on developing «Key Market» with David than I had spent designing the earlier games and I think the final game fits well into the Key range. «Key Market» is quite a tight game and is more ‘scripted’ than the other games in the series. I had promised David at the start that the game would be published under his name, as I know from my experience with Hans in Glück and «Aladdin’s Dragons», that this recognition is important to the game’s creator. So I am just listed as developer for this title.

The second edition of «Key Market» was released in 2019. Why was such a decision made? What changes were made to the game?

The first edition of «Key Market» was published in 2010. The gaming world and R&D Games were both a lot smaller then and just 1,000 copies were produced. It was a troubled delivery as the manufacturers used a new supplier for the wooden pieces. The wooden pieces were of questionable quality and delivered late and the manufacturer never used this supplier again. All the copies were pre-sold prior to its release at Spiel. «Key Market» was well received by gamers and inevitably became expensive to buy second hand.

Consequently, in August 2017, when Boardgamegeek’s ‘Geek of the Week’, I invited gamers to thumb the «Key Market» cover image, promising to issue a second edition on Kickstarter if there was sufficient interest and 500 thumbs were received. In the event the total was well over 1,000 thumbs.

The structure of the «Key Market» second edition game is largely unchanged from the first edition. However, four new guilds have been added to the game and the original guilds reviewed so that the powers and points are more balanced, to give an even more challenging gaming experience. The second edition also includes a set of wooden meeples for gamers who would prefer to use these instead of the worker counters. The rule book has been largely re-written and streamlined.

Any other games of yours you would like to revisit?

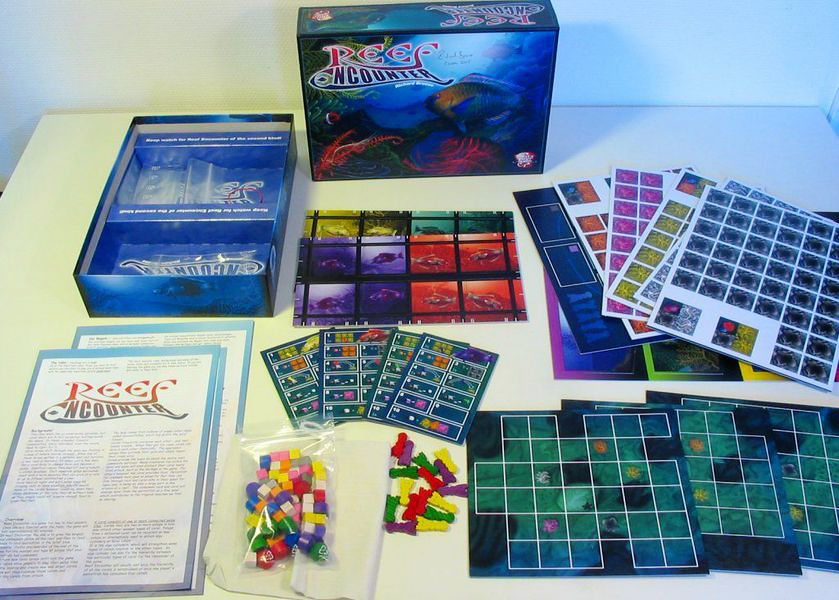

The «Key Market» second edition features a new R&D ‘gold’ logo to denote the re-issue. It is possible that I might re-issue «Keydom/Aladdin’s Dragons», «Keythedral» and «Reef Encounter» at some point when I have the time between creating the new games.

Last year marked the release of the official Russian edition of «Keyflower». The game was well known before, but still it can be called a notable event. Tell us have you expected this kind of success? What allowed the game to become popular?

Sebastian and I had a positive feeling whilst we developed «Keyflower». But it is not easy to predict how successful a game can become. However at an early stage I thought it could reach the BGG top 100 games, although Sebastian took a lot of convincing. In their time before, both «Keythedral» and «Reef Encounter» had reached the BGG top 100 games. Of course this is more difficult now that there are so many more games published and the ratings tend to favour heavier games than those in the Key series.

Can it be called revolution or evolution of the Key series?

I prefer ‘evolution’ to ‘revolution’. And as mentioned earlier, I think the series will continue to evolve. The main ‘hook’ of «Keyflower» is undoubtedly the Sebastian’s bidding mechanism and its subsequent development into the dual use of the ‘keyples’ for both bidding and resource generation.

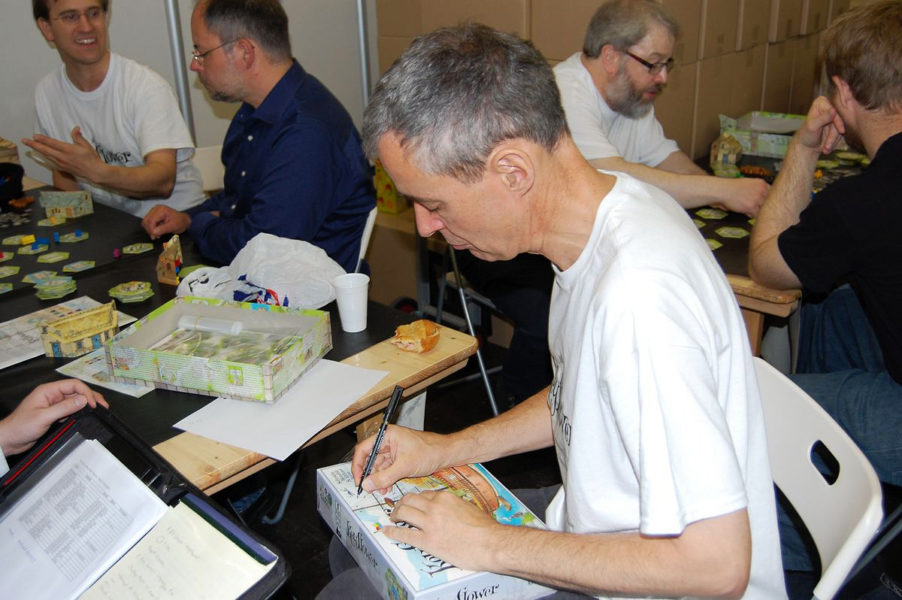

«Keyflower» was the first game you co-designed with Sebastian Bleasdale. What initiated this collaboration?

It was a similar story to «Key Market». I play tested a game of Sebastian’s called «Turf Wars», which included the bidding mechanism. I contacted Sebastian afterwards with several ideas I had for using the mechanism in a larger game and would he be interested in working together to follow through these ideas.

«Keyflower» is notable for its interaction. The game wants the players to actively place their meeples on other players’ villages, however this kind of interaction does not feel aggressive and doesn’t make you feel offended. Can you describe it as your trademark?

To an extent. I like my games to feature player interaction, but only in a positive way. I generally do not design any negative or ‘take that’ actions into my games as it usually creates a negative feeling also. However, it can be done well. An example is in last year’s game «Architects of the West Kingdom» from Shem Phillips and Sam Macdonald, where players must capture their opponents’ pieces to generate further resources for themselves.

More and more often we get games without any interaction between players and the gameplay is more ‘solitaire’. What is your view on that? Why does this kind of games seem to gain popularity?

I think more solitaire games are popular because players like to be able to plan their turns without any interference from their opponent’s. So the winner is simply the player who can optimize their moves best. I enjoy these games also, but they can lead to too much analysis paralysis with the wrong players. For my own games I prefer designs which place reliance on other players also, for example in «Keyper».

Are there any plans to design another game not based on the Key universe?

I’m sure it will happen. A game has to fit into the Key universe to become a key game. i.e. positive player interaction, a little luck omly, workers/keyples operating in a medieval environment or one of a similar scale (such as «Key to the City – London»). There is no violence in Key games, so, for example, «Reef Encounter» could not have become a Key game as the corals attack each other and the shrimps get eaten!

How big is R&D Games? Who came up with the name? And what is that chameleon on the logo?

I launched R&D Games as a label to publish my own game ideas. My first published design was «Chamelequin» (1989), an abstract game with the eponymous creature from the game featuring in the recent R&D Games’ logos. The names comes from Richard and Dawn. Dawn was my wife, but the initials also double up of course as Research and Design, which sums up the process. I run R&D Games as a part time hobby as I have a ‘proper’ job also. I do the designing and/or the developing, plus the graphics and realisation. With Juliet and then Vicki creating the original illustrations.

Do you have any spare time to play yourself? If you do, what games do you prefer and why?

I have at least one games night each week. My favourite games are Euro games, similar to those that I design. I’m also always interested to learn what my fellow designers are creating.

My long term favourite is «Rummikub», as this can be played with family and non-gaming friends. «Abluxxen» and «Take it Easy» fill this spot also. There are lots of games I enjoy playing. I’m a member of the ‘Cult of the New’ and am usually playing newer games. Also, I play my own games a lot during the development proves and these only get to be published if I have enjoyed them!

I don’t generally have many expectations about other games. There are so many good games now that if a game is disappointing it simply doesn’t get played again, quickly gets disposed of and does not stay on the memory for long!

Thank you, Mr. Breese. We wish you luck in all your endeavors, Key-related or not!

My pleasure. Thank you for your interest and enthusiasm and for your work in compiling these questions.